Act 1 – Discovering Martha

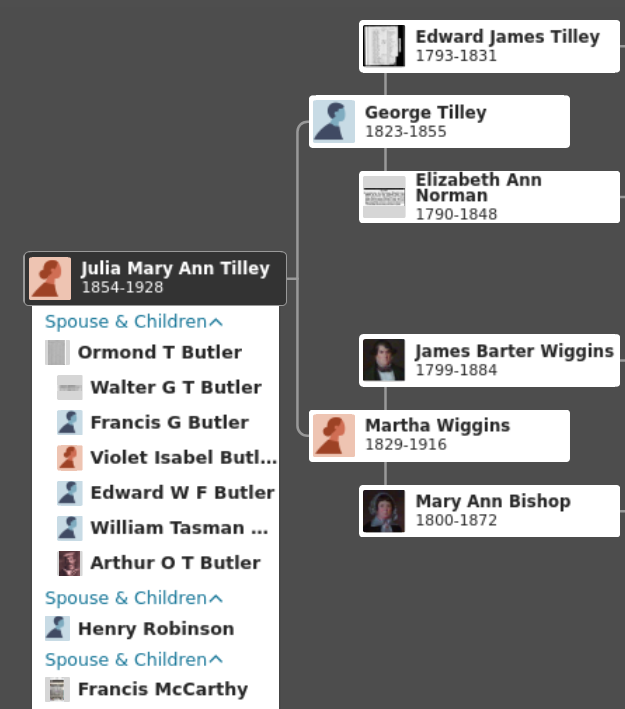

When I found that the parents of my great-great-grandmother Julia TILLEY, were George TILLEY and Martha WIGGINS from Tasmania, it was easy to find information about George, as there were newspaper reports when both he and his father Edward died in separate accidents at sea.

Originally I was confused about who “my Martha Wiggins” was because there were two girls of that name in Tasmania in the right time frame. At first it seemed that Martha born in 1825 to Thomas Wiggins & Susanna Welch must be the correct one as she would have been about 20 years old when the 22 year old George Tilley married in 1845.

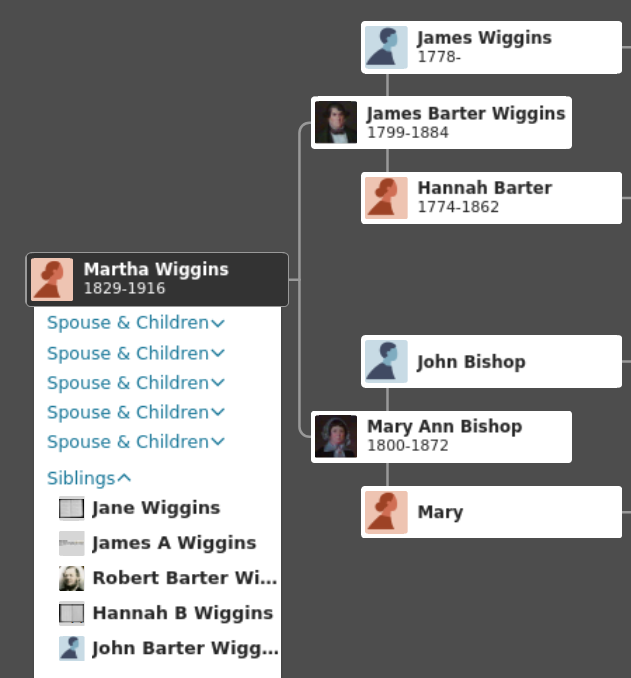

However, further evidence on certificates, and newspaper reports of George’s death in a whaling accident confirmed that his father-in-law was James Wiggins. James’s daughter was the other Martha Wiggins born 1829 in England, so she was only 16 when she married George.

After George Tilley’s death I lost track of Martha as there was no record of the death of a Martha Tilley in Tasmanian records.

I continued to follow the trail of their youngest daughter Julia Mary Ann TILLEY, who married my great great grandfather Ormond BUTLER in Tasmania about 1872 and had 2 sons, born in Hobart. Some time after the birth of their 2nd child, Francis, in February 1875, Ormond and Julia came to Melbourne where their first son Walter died in September of that year.

They went on to have a daughter and three more sons in Melbourne, and when Ormond died at the age of 32, in 1884, 30 year old Julia was left to bring up 5 children between two and 10 years old. The youngest child, Arthur Ormond, was my grandfather’s dad, who died at the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916.

Tracing Julia and Ormond’s grave at the Melbourne Cemetery in Carlton I discovered that they were buried with their 2nd son Francis and a woman named “Martha FOSTER”. No Fosters in our family as far as I knew at that time, so who was this mysterious lady? After about half an hour of searching through records of other relatives of Julia – sisters, aunts, cousins – for someone named Martha, I suddenly realised it must be Julia’s mother the elusive Martha Wiggins.

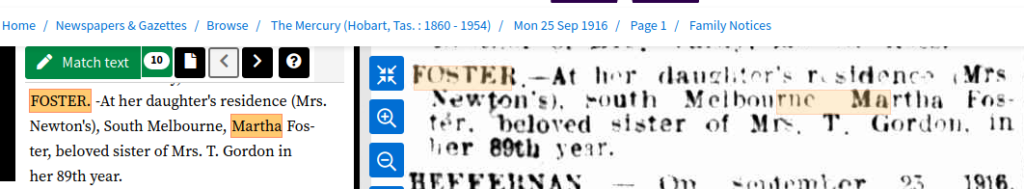

Further checking revealed that Martha had also died in 1916, at the age of 87, just 2 months after the death of her grandson Arthur. So 1916 wasn’t a good year for Julia.

Although Julia had two more husbands in later life it was probably Martha who helped her bring up the children in the 11 years after Ormond’s death and before she remarried for the first time.

Act 2 – Marriages and Mayhem in Old Hobart Town

Martha was born in Sussex, England in 1829. Her father James Barter Wiggins was transported to Tasmania in 1831 on the convict ship “Argyle”, and in 1834 his wife Mary Ann Bishop joined him there with their four young children, Jane, James, Robert & Martha. After James was freed, he and Mary Ann had another two children, Hannah & John. He gave up his former life of petty crime and settled down to become a ‘respectable’ citizens of Hobart Town, and became Licensee of a Pub.

Portraits of James & Mary Ann are in the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart – more...

See my previous post for more information on the portraits

At the age of 16 Martha was married to George Tilley a local mariner and they had five children. Then in 1855 when their youngest daughter Julia was less than a year old, George was killed in an incident with a whale of the coast of Tasmania. In an odd coincidence his father Edward Tilley had been drowned in the D’Entrecasteux channed off Hobart in 1831, when the ship he captained capsized in a storm.

The following year Martha married James Claridge, who had arrived in Tasmania under the Immigration Bounty Scheme – see details...

About Tasmania, Australia, Immigrant Applications and Bounty Tickets, 1854-1887

After transportation of convicts to Tasmania ended in 1853, the island turned to a bounty system to attract needed labor. Under this system, immigrants contracted to work for employers who paid for or subsidized the immigrant’s passage. The government also offered a bounty that could be claimed by the employer once the immigrant arrived and passed an inspection. Later, bounties included land for immigrants. By these schemes, the government and settlers of Tasmania hoped to both meet the island’s labor needs and improve the class of immigrants who settled there.

Immigration societies formed to help promote immigration, and agents operated in England and other countries to recruit immigrants/employees on behalf of Tasmanian residents. Societies or agents sometimes purchased blank bounty tickets from the government and then looked for potential immigrants for whom the bounty would be claimed once they arrived.

James probably met Martha’s father as part of his sales job getting orders from publicans for his employer’s supplies. Unfortunately within a year James was convicted of embezzling about 900 pounds from his employer, Mr Carter. His yearly wage was 100 pounds, but his main defence was: “the large expenses he was obliged to incur in soliciting orders from the publicans, customers to Mr. Carter”. Apparently the “salesman’s business lunch” was a thing in the 1850s too.

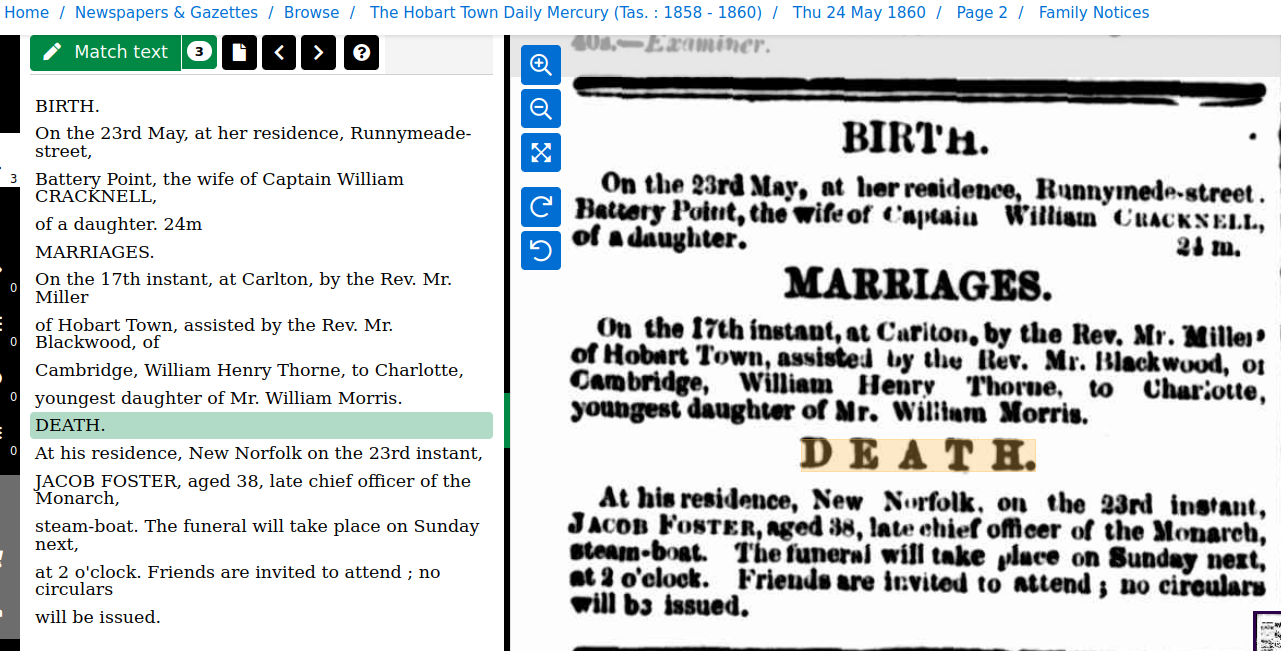

With her husband in gaol and five children to support, young Martha decided to take up with Jacob Foster and proceeded to have 2 more daughters, Alice in May 1858 and Selina in April 1860. (Father described as Sailmaker/Mariner). Both babies were registered by Martha without given names and recorded by the registrar as male (the default for an un-named child?) Alice was baptised in October of 1858 at holy Trinity Church, but I can find no baptism for Selina, perhaps because Jacob Foster died in 1860 a month after Selina was born.

Another daughter Caroline born in 1863 is described on her birth registration as daughter of Margaret Foster (formerly Wiggins) and John Foster (Blacksmith). A fourth daughter, Ada Esther, born in 1865 is registered as the child of Martha Foster and John Bank (Blacksmith), could he also be the father of Caroline? The informant on Ada’s registration was the baby’s half-sister Eliza Tilley, who at 17, it seems was less inclined than her mother to obfuscate the facts on official certificates.

James Claridge died in 1867 from the DTs, so seems to have taken up his old drinking habits after his release from gaol. He is described in a brief notice in the Hobart Mercury Newspaper as the postmaster at Latrobe in northern Tasmania (near Launceston). There is no indication that he and Martha got back together again.

The next record of Martha is in 1870 when she married again, to 28 year old blacksmith William Waterhouse Hutchinson. By this time Martha was about 41 years old and had 4 children under 12 dependent on her, although she appears to have neglected to tell her new husband the full details of her childrens’ paternity. Not surprisingly things didn’t go well with this marriage, especially when William found out that Martha was receiving support payments from the father of the youngest 2 children.

In October 1871 Martha appeared in court to petition for Hutchinson to be “bound over to keep the peace”. A few months later Hutchinson was in court again charged with assaulting Martha’s father James. Both court cases makes interesting reading with claims and counter claims of threatening behaviour, drunkeness and neglect on all sides. The also indicate that by July of 1872 Martha had gone to Melbourne to live with the reputed father of her youngest children. (read case details)

LAW INTELLIGENCE. (1871, October 19).

The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), p. 2.

SURETIES OF THE PEACE – Martha Hutchinson

prayed that her husband, William Hutchison, might

be bound over to keep the peace towards her, he

having used threatening language to her on the 11th

instant

Mrs Hutchinson stated that she had been living

with her husband in High-street. On Saturday last

he made use of a foul expression to one of their

children, whom he had sent on a message, and wit-

ness checked him for it. He became very angry,

threw a stone jar at her, and struck her in the mouth

with his open hand. He also threatened that he

would be hanged for her, and she had not since gone

home. She was still in fear of his doing her bodily

harm, and made the complaint purely for her own

protection

Mrs Ward, a neighbour, who had been called in

by the last witness on Saturday afternoon, stated that

Hutchinson threw a jar at his wife, and struck her

in the mouth The man and his wife had some

words about the children. Defendant did not say in

witness’s presence that he would be hanged for his

wife. The parties frequently quarrelled.

The man said he went home on Saturday morning

and found his wife drinking. No dinner was pre-

pared, and they had some words on the subject, when

she aggravated him, and he threw the jar into her

lap afterwards she further provoked him, when he

struck her in the mouth with his open hand.

Michael Sinnott was called, but he had seen

nothing of the quarrel. He saw the two women, Mrs

Hutchinson and Mrs Ward go into a public house

just after the quarrel. Matthew Smith, another

witness, stated that he saw nothing of the dis-

turbance.

The Bench called upon the defendant to enter into

his own recognizance of £10 to keep the peace towards

his wife for six months.

POLICE COURT. (1872, May 15).

The Tasmanian Tribune (Hobart Town, Tas. : 1872 – 1876), p. 3.

Before W. Tarleton, Esq., Police Magistrate, and

H.Cook, Esq., J.P.

James Wiggins complained that William Hutch-

inson assaulted him on the evening of 20th April.

Complainant is an old man, of about 60 years;

defendant young, about 28, and son-in-law of com-

plainant.

Defendant pleaded not guilty.

Mr. Fitzgerald appeared for complainant, and

Mr. Moriarty for the defendant.

After a few introductory remarks from Mr.

Fitzgerald,

James Wiggins was called, and deposed that on

the evening of 20th April, about 7 o’clock, he saw

defendant near the door of his (witness’) public-

house. Witness told him he ought to be ashamed

of himself for starving his grandchildren and

ordered him out of the house, when defendant

struck him a blow on the chest saying, ” Take

that you b— old dog.” Defendant then called

two dogs which were with him, and told them to

seize him. No provocation was given to defendant.

He did not go, but Constable Jackson took him

in charge for using obscene language. I saw

defendant’s dogs outside before he struck witness,

but did not see the constable before he came to the

door. Have had no dispute with defendant since

he married my daughter. Never made use of any

bad language towards him, and never on any

occasion said he cut defendant’s head open

with a “neddy.” Witness struck the defendant

when his dogs worried him, only struck to keep

the dogs away, and in self-defence. Witness did

in Trabuco’s shop say in presence of Mrs. Bennett

that he had given defendant a hiding, and would

lock him up. It was too dark for witness to see

whether they were sheep or bulldogs. Heard

defendant say to the dogs ” Go on and drag the

old dog out” Witness did not recollect seeing

F. and G. Smith in his house before the assault

and did not in their presence utter threats towards

defendant.

Constable Jackson deposed that he was on duty

on his beat in Collins-street, on 29th April. About

7 pm. he was near Wiggins’ Hotel, and heard

defendant make use of bad language. Witness

took him in charge and locked him up. While

crossing the road saw defendant strike – Wiggins,

and try to set a dog on him, saying “sieze him.”

Witness never received a message from Wiggins to

be at his house. Wiggins had a good sized stick

in his hand, with which he was guarding himself.

Defendant was sober, He was fined 10s. 6d. next

morning for using obscene language.

Mr.Moriarty asked the Bench whether two

cases could be made out of one matter, as defen-

dant had previously been fined for an offence —

using obscene language.

The Bench decided that in this matter it could

be done, when

Mr. Moriarty pointed out the coincidence of

Jackson being on the spot, and said it looked

very much like a pre-arranged affair.

Mr. Tarleton: It was very fortunate. If the

constable had not been there the papers would

have cried ” Where’s the police!” (A laugh.)

Mr. Moriarty then called

Mary Ann Bennett, who swore that on the even-

ing in question she was in Trabuco’s shop. Mr.

Wiggins was walking up and down in front of the

shop. Heard him say he had given “the crippled

dog” a good hiding, and that he would feel the

weight of his stick in the morning. Did not say

defendant had assaulted him. Defendant is a

cripple.

By the Police Magistrate : The expression was

“the crippled dog” not “the cripple’s dog”

Frederick Smith deposed that about four

weeks.ago he was In Wiggins’ public house with

his brother and Hutchinson, when Wiggins

pulled out a life preserver and struck on, the

counter, saying he would cut Hutchison’s

skull, open, if ever he came to his house again

Witness went into Wiggins’ by himself first, -when

Wiggins’ demenour was very quiet. After he had

been there ten minutes his brother and Hutchinson

came in, and it was then that Wiggins grew

angry and threatened defendant.

This being the case, the Magistrate consulted,

and decided that as an assault had undoubtedly

been committed, they would fine defendent 20s and

costs.

By July of 1872 Martha had gone to Melbourne presumably with the four youngest daughters, and William was in court again to argue against forfeiting his surety (bail) of 10 pounds from the original case bought by Martha the previous year. After some legal argument about whether William could give evidence the newspaper report continues:

William Waterhouse Hutchinson, the defendant,

examined by Mr. Moriarty : I am a blacksmith by

trade. Some time ago I was married to Miss

Wiggins. I afterwards discovered that she had been

receiving maintenance at the Post Office for two

illegitimate children, which was a source of grievance.

I was bound over about nine months

ago to keep the peace towards her, on her evidence,

but I did not use the language imputed to me.

Previously to that she was in the habit of coming

home drunk, and I had no meals prepared, and no

comfort at all in my home. She was in the habit

of visiting improper houses. I discovered a letter

from a person in Melbourne to my wife. It dropped

from her bosom. I showed it to Mr. Reed, a

neighbour. I have lost the letter. It was an in-

vitation to her to come over to Melbourne when

she was ready, and he would send her passage

money. She had since gone over, and was living

with the man in Melbourne. On the occasion of

the assault she struck at me with a short poker,

and, in defending myself, she fell on the floor. I

had no evidence to contradict her statement. Since

I was bound over she came home drunk, and I

went round to Mr. Dorsett to come and prevent a

breach of the peace, and I walked about all night

rather than break the peace. I am not in good

circumstances, and have already paid £1 3s. to the

Sheriff. I have nothing to pay the £10 recog

nizance. I was fined £2 for the assault.

Mr. Dorsett, Sub-Inspector of the City Police,

proved that he had known defendant 14 or 16 years ;

he was an industrious peaceable man, and not quarrel-

some. Witness proved that his wife received money

from the putative father of an illegitimate child, and

since defendant discovered it there had been no

peace between them. Witness confirmed defend-

ant’s statement as to his calling him up to prevent

a breach of the peace The woman had gone to

Melbourne.

John Reed, who resides in the same neighbour-

hood as defendant, proved that defendant showed

him a letter which had the Melbourne post stamp

on it. He confirmed the other evidence as the the

habits of the woman and her husband.

Their Worships, after hearing this evidence,

determined under the circumstances to remit the

amount of the recognizance and discharge the

defendant, on paying the Sheriff’s fees.

Defendant was then discharged.

Act 3 – Secrets Taken to the Grave

What we Know we Don’t Know… and What we Don’t Know we Don’t Know…

As official record keeping became more regulated people seemed to become better at fudging the truth to cover their indiscretions and moving to a different city always provided a chance for a new start. Martha called herself Mrs Foster for the rest of her life after coming to Melbourne, so how long did she live with Banks if he was in fact the man she came to Melbourne to live with? The 2 oldest girls, Alice and Selina, at 14 & 12, must have known he wasn’t their father unless he used the name Foster too. They would also have been old enough to be aware of her legal marriage to William Hutchinson just two years before, although they could have been living with their grandparents, James and Mary Wiggins, or one of their older half-sisters during the time Martha was with William.

The youngest of the girls, Ada died in 1875, at the age of 10 (interestingly Martha used the name William for Ada’s father on the child’s death certificate), but the other 3 girls would presumably have had contact with their half-sister Julia after she and Ormond arrived in Melbourne in 1875, so they might have gained some knowledge of the past from her.

At the time of her death Martha was living with her daughter Selina, who had married John Newton. A notice was inserted in the Hobart Mercury by Martha’s youngest sister, and only surviving sibling, Hannah who married her 2nd husband Thomas Gordon in Tasmania in 1875.

Martha’s death certificate list only 2 marriages, her first to George Tilley, listing the 5 eldest children, and a 2nd to Jacob Foster, with the 4 younger girls listed as his children. The information on the certificate was probably provided by Selina or Julia, and contains a fair bit of guesswork and/or covering up.

Her age at first marriage is given as 19 rather than 16 – probably a guess based on the ages of her eldest children. Her age at second marriage is given as 28, about the time she married James Claridge and just before the birth of Alice Foster. Whether they were guessing about the supposed marriage to Foster or knew it never happened but “covered over the cracks” as many families had in the past, we may never know.

Categories: Pieces of History

Leave a Reply