I recently stumbled across a review by Richard Watts of an exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and Gallery in 2019, Which juxtaposed the works of indigenous artist Julie Gough with non-indigenous works from the gallery’s collections. Watts assessment of the exhibition was that it –

“interrogates colonial history and the impact of colonisation on Tasmania’s First Peoples – then and now”

He further describes one such juxtaposition –

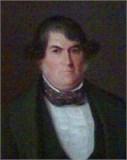

“Knut Bull’s portraits of James Barter Wiggins (circa 1851), a Hobart builder, contractor and publican, and his wife, Mrs Mary Anne Wiggins (nee Bishop) (circa 1853) depict the prosperous couple some two decades after the Black War was fought in Tasmania. The pair are soberly dressed, double-chinned, their eyes cool and confident – but what did they see earlier in their lives? What did they know?

Beside the oil on canvas portraits of Mr and Mrs Wiggins hangs another painting: Thomas Napier’s Woureddy & Trucanini (1832). Less finessed than Bull’s work, its placement in the exhibition, and the cruder execution of its subjects, perhaps implies that the artist considered his subjects of less importance than a doughty Hobart burgher and his wife. Today, it is a work of far greater significance. “

The full review can be found here.

https://www.artshub.com.au/news/reviews/review-julie-gough-tense-past-tmag-dark-mofo-258168-2363487/

I originally saw the Wiggins portraits, more than 10 years ago, as part of an exhibition of pioneer families of Tasmania. Presented in a more benign setting, without reference to the struggles of the indigenous inhabitants of the island.

Back then my interest in them was mere curiosity at the coincidence between their names and that of my 3 x great grandmother Martha Wiggins. I had decided at that time, that my Martha was not related to this couple, but later research proved that she was in fact one of their daughters.

My exploration of the family history paints James and Mary Anne in a slightly different light. While they may be described as ‘prosperous burghers’ in the 1850s, their origins were far from the implied connection to the landed gentry of the “Old Country”.

James was transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1831 for crimes of larceny, and his wife followed him three years later with their four young children. Like many of our convict ancestors, they used the opportunity of transportation to a new country to build their lives up out of poverty and create a better future for their children, and while this was no doubt done at the expense of the original inhabitants of the land, the suggestion that they had any direct involvement in the outrages committed by government officials in the name of the Empire is something of an exaggeration.

Most poor people of the time had much less say in what was done by their government than we do today, and they were also victims of the excesses of Empire that created the social conditions in Britain, described so clearly by Charles Dickens.

My ancestors certainly had their faults and I don’t want to paint them as pillars of the community, but nor can I accept the implication that they were accurate representatives of the all that was wrong with early Australian society. Our history is a jigsaw puzzle of good and bad, but simplistic “black and white” contrasts of the Noble and the Evil, ignore the shades in between; of many people on either side of the colonial divide, trying to survive from day to day.

Comments in social media recently have prompted me to think about the place of Pride & Shame in genealogy.

Of my 16, great great grandparents 13 are vanilla British – Irish, Scots, & English, 2 are Australian born, but of the same British heritage, and my one “exotic” ancestor is a Frenchman from Caen. I am neither “Proud” nor “Ashamed” of this. It is just a FACT. What’s more, a fact that is totally beyond my control.

Something that makes me cringe when I hear people proclaim themselves PROUD of their heritage is the unspoken implication that anyone of a different heritage should be ASHAMED. We are entitled to be proud of are our own personal achievements, and perhaps to bask in some reflected pride in the achievements of our family members. As for shame that should be reserved for anything we’ve done wrong deliberately while knowing that there was a better alternative to our actions. Honest mistakes are not a cause for shame they are an opportunity for improvement. The mistakes or wrongdoing of past generations are also not cause for our shame, but learning opportunities for all of us to do better in the future. The real evil is to refuse to learn from history.

#Genealogy #FamilyHistory #Australia #Colonialism

Categories: opinion

Leave a Reply